I promised myself that I would not write a blog post today. And then I read the speech Andy Haldane, Chief Economist at the Bank of England made yesterday before getting out of bed this morning, and my resolve failed.

I mentioned my opinion of Haldane in my comments on inflation, made yesterday. Haldane's comments yesterday were in a paper entitled 'Inflation: A Tiger by the Tail?' He obviously fancies himself as the new Tigger. It's an uncomfortable performance.

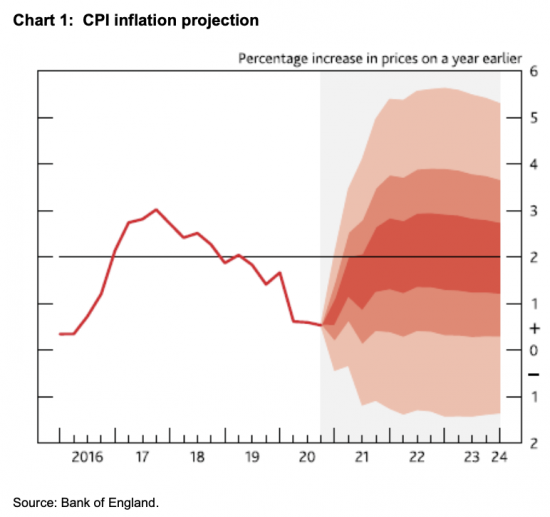

First, let's look at the official Bank of England projection:

Remember the Bank is required to deliver 2% inflation, and what it says is that this is exactly what it will do, plus or minus, or as Danny Blanchflower reminded me yesterday 'all depending'.

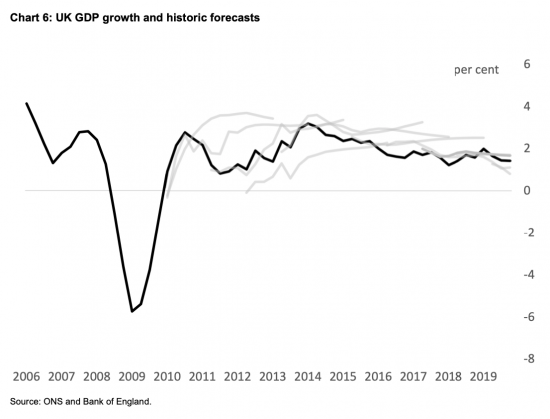

There is an important caveat to this forecast. Haldane includes this chart in his speech:

Every single growth official forecast after 2009 was overly optimistic, usually by some way, until Covid came along. The ability of the Bank, Treasury and OBR to believe that austerity, their supply-side reforms and QE would deliver a boost to growth has been astonishing and literally all of them failed. I think we need to read everything Haldane says now in that light. This is a person who has overseen the slowest recovery in 300 years, and is now sitting on the worst recession in 300 years.

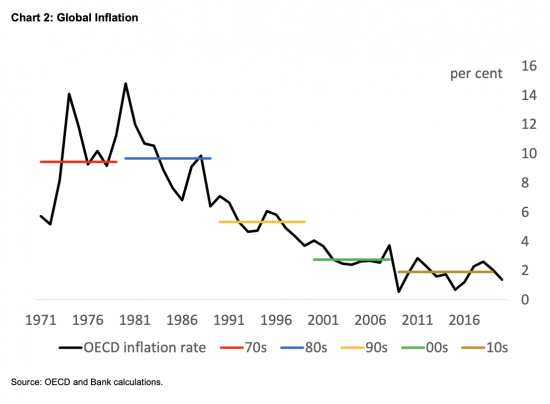

History is also against his view. As he also notes, the trend in inflation is d0wnward:

The trend in interest rates matches that, near enough: the two are, of course, related.

So why does Haldane have his innerspring coiled, Tigger like? He thinks it is the increase in the money supply, created by QE and government-backed lending that will deliver inflation. He notes:

Interestingly, this rapid growth in central bank money creation was not mirrored in money spending growth in the economy. In the ten years prior to the Covid crisis, narrow money globally rose by over 150%, while money spending globally rose by less than 50%. In the UK this contrast was starker still, with central bank money rising by around 200%, while money spending rose by less than 50%.

So, there is a lot more money around, albeit money that is not spent. But, he thinks that is going to change. One reason for this is that he still thinks that banks are intermediaries (he use the term several times in the paper) despite the fact that the Bank of England shattered this myth in 2014. So, he thinks there will be more lending now because there are more deposits, having failed to note that the recent growth is entirely because of the supply of government guarantees, most of which are about to be withdrawn.

For another reason, he draws on Milton Friedman, who he notes described money as 'a temporary abode of purchasing power'. Haldane thinks temporary means 'for the short term now'. He is encouraged by the fact that almost all saving has been in cash.

And why? He notes that households have accumulated £150bn of savings during this crisis and businesses £100bn. I suspect he understates the sums in question unless the foreign sector has also been saving in the UK. But the important point is that he believes that theses sums are about to be spent. Or rather, he thinks households will spend, as he seems to have less confidence in a growth in investment.

His logic is bizarre. He recognises that 'savings are highly unevenly distributed across UK household' but then says 'the Covid crisis has resulted in stronger, not weaker, balance sheets, at least for the average household and company. This is likely to increase, not reduce, their willingness to take risk'. In other words, the animal spirits of most households are about to be let loose.

It was at this juncture that I realised I was reading the work of someone who I think I can appropriately describe as a fool. The reason is that averages are not the basis for forecasting, for reasons he has noted, to which I refer. It is, of course, true that there are some households and businesses with considerably stronger balance sheets now than they had before this crisis. Those in this position are considerably better off. But the majority, by some way, are not.

Over 80% of businesses are likely to have taken on borrowing during this crisis. They are not better off. They have a mountain of debt to service.

And there are millions of households in the UK now facing debt crises. The sums that they owe might, individually, be much lower than the average gains for the best off households. But here comes the point where Haldane proves himself the fool: he averages across the population as a whole and so says there is a wall of money to be spent.

As I have suggested before now, no doubt amongst his rich mates this is true. But in general, a small treat or two apart (and of course they will happen) that is not true. Averages in a situation like this give no hint as to likely behaviour. Distribution does.

And the distribution of saving is heavily skewed, with most being amongst those with the lowest marginal propensity to consume because they are already wealthy and can consume all they want anyway.

I quietly despair at the poverty of this thinking.

I also despaired when noting that Haldane does not realise that banks do not intermediate.

I also despaired that his chosen references are to Friedman and Hayek.

But most of all, I despaired because markets are being influenced by this complete nonsense. They actually believe that he knows what he is talking about. But, of course, those in financial markets share his current life experience.

In the real world people will not take risk. There are three reasons.

First, R is going to increase rapidly after school reopening, I suspect. The chance that lockdown will end in June is remote, in my opinion.

Second, even if it does the end of furlough is going to be bad news for many. Unemployment is going to increase.

Third, for those businesses with poor balance sheets reopening is going to be tough. The economy is not in for a smooth upward ride.

Risk will abound, then. And so people will not be spending.

Of course, at ‘all depends' but I am not an optimist, and the evidence stacks heavily in my favour.

The chance of inflation is low. But so too is the chance of economic good times. And Haldane has always called that wrong.

The worry is that Sunak will base policy on this nonsense. Then this becomes dangerous.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Entirely agree. It has never been more impotant to disect the false picture that economists paint with averages.

Most wealthy households do indeed have big savings, but their spending will more likely return to normal in terms of holidays and eating out, rather than providing an exceptional boost.

Those who have been furloughed or laid off are now in a pit of debt, which will affect their spending for years to come, making an economic bounce most unlikely.

Perhaps the strongest evidence that Haldane is woefully optimistic are the banks. Far from preparing for a bounce, they are facing a double whammy from collapsing commercial property values and a mountain of bad business debts secured on them. Add huge provisions being made for bad personal debt, and most banks are now rapidly restricting lending and/or tightening their lending criteria.

The only factors that might boost inflation temporarily are rising cost of imports due to Brexit or weakness in the pound, which will make stretched household budgets even tighter. A real recovery can only start from the bottom up, by introducing a basic income, to rebuild our communities and stimulate demand. But there is no indication that either of the two main parties will consider this, even though the majority of voters would now support it.

Puts me in mind of the Keynes quote

“Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back”

maybe a bit harsh; then maybe not considering the damage it could do.

Yesterday I came across the expression “Murdoch’s Proles” which was being used to describe a theory of existence held by the rich few and their managerial gophers which is basically feed the people shallow thinking nonsense so they behave like livestock rather than human beings.

As if on cue to confirm this theory there’s been a spate of opinion pieces in the newspapers these last few days which are all saying the same thing the government must get its books in order otherwise there’ll be economic damage. Notably, of course, exactly what the “damage” will be is never spelt out or if it is it’s that abnormal inflation is on its way!

Interestingly you never hear this argument in normal times when the amount of debt held by private sector banks grows larger year after year. These banks are never asked to pause lending until they get the quantity of their lending below a certain threshold for fear economic damage will ensue. Nor of course does anybody bother to ask if such a policy of restraint was followed along with one on government spending how this would affect the desire to save by the private sector. Here’s a few of the “Murdoch Prole” articles that have been appearing in recent days:-

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/feb/25/tax-rises-party-uk-rewards-voters-pandemic#comments

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/budget-rishi-sunak-kenneth-clarke-b1808408.html

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/feb/26/sunak-to-use-budget-to-start-repairing-the-uks-public-finances

Very clearly the whole purpose of these articles including Haldane’s is to destroy trust in government a theme Rupert Murdoch has spent a lifetime career pursuing and especially notable in his American Fox News TV channel supporting Trump’s campaign the Democrat’s “stole the vote.” Notable that is until the voting machine and voting software companies began a huge financial compensation claim court action against Fox News for slander!

Re that article in the Independent (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/budget-rishi-sunak-kenneth-clarke-b1808408.html): It’s disappointing from a journalistic point of view. The reporter/political editor does nothing but transcribe Lord Clarke’s fulminations. He makes no attempt to seek out countervailing views — though many of the commenters provide them.

We all know that the BoE inflation forecast MUST be centred at 2%. That is the target and if the forecast were different then the question would be “why aren’t you altering policy if you are forecasting a ‘miss’ on inflation”. It really is the most useless chart out there….. against some pretty stiff competition.

Could the ‘Tiggers’ be (deliberately) confusing “change” and “level”?

Will post lockdown spending be higher than today? Probably. But that is higher from very depressed levels. Will it be higher than previous levels seen before COVID? Probably not… for the reasons that you suggest.

Will I spend more? Yes – I will eat out again….. but even I only eat one dinner a day, there is no catch up. But I am one of the lucky ones. For many the outlook is grim.

To prove it, we really need is savings data by wealth level. Or simply, what is the median (rather than aggregate) increase in savings over lockdown? I am going to guess it is zero (or close to). Does such data exist?

Given that we’re told the bulk of the currency created for the economy is by private sector banks why aren’t they being told first before government to get the quantity of their money creation down and a freeze imposed on future lending till they do?

Surely the BOE has a model which segments the economy and behavioural psychologists that can predict the behaviour of each segment? Most of the population are scared witless and will be incredibly cautious about splashing the cash, except the happy few bloated plutocrats who are likely to leave these shores to find some sane harbour.

You would think their local agents were telling them this

I am baffled….

Which reminds me of my new word; plootocrats. Self-explanatory, I think.

Haldane is I think in his own way just acknowledging something that is palpable out here: that people have had enough – they are looking for the big break to get back to normal. Or at least those who want to be told that that is to happen and are chomping at the bit now – even now breaking rules as they go along.

However, alongside that is what has also be mentioned here already – fear – the lag between getting back to normal and the ending of support as the dust settles and employers for example see the true cost of lockdown.

I’m not sure that they’ll be a spending jamboree at all. Especially with our wonderful ‘buzz-kill’ chancellor.

My suspicion is we will be in another lockdown before the spending might ever got going

Agreed.

There’s an old saying about not being able to herd cats.

It also applies to Covid 19 and the like.

As you say distributions matter. The pandemic has worsened the divide between those with wealth and those without.

Most of the new money causes asset price inflation which only helps those with assets and does nothing for the wider economy. Conveniently for the wealthy asset price inflation is not even included in our flawed inflation measure.

The spending we need is spending on services and investment in local communities. Both the BoE and conservative chancellors are too embedded in the ideology of big city finance to be able to understand what they are doing wrong.

Agreed

And this is why the Recovery Bond matters. It drains money out of the system……. but from wealthy savers and prevents asset inflation WITHOUT depressing real economic activity (as long as the government keeps spending/investing on useful stuff).

In the past we had just one tool – interest rates – to control two variables asset inflation and CPI inflation. History shows that with CPI under control asset prices ripped. But in fact we have more tools – government spending, taxation, interest rates/bond issuance – so by tweaking appropriately we can try to control BOTH CPI inflation and Asset price inflation.

(Indeed, we could add other tools, too like controlling credit advanced on margin lending or mortgages and it is interesting to note that they are having this discussion in NZ).

We really need to get away from the last 40 years where a single interest rate set by Central Bankers was the only variable that could be tweaked.

Spot on

Johnson/Sunak’s decision this week not to suppress the virus, but to ‘live with’ daily new infections in the thousands is a disaster for the economy.

Sending all children back to school in a big bang, and setting self fulfilling dates for other reopenings will, as their own advisers, (and Richard) suggest, will produce a further wave of infections, hospitalisations and deaths in summer/autumn, and a further lockdowns, dampening the economy again.

Independent forecasts for GDP for 2021 range from 0.5% to 6.1% (avge 4.4%) , unemployment 6.6% and for 2022 1.4%-7.6% (avge 5.7%), unemployment 5.6% .

Such massive uncertainty shows the sheer ignorance and folly of not suppressing the virus to as low a level as can be controlled without lengthy universal lockdowns (eg NZ, Aus, China, S Korea , Taiwan, Finland etc etc.)

Haldane may well turn out to be overly optimistic but I do not see how calling an intelligent person a fool adds to the quality of the debate. He simply has a different view to the central BoE view and the one that we both share and the average comment is simply taken out of context, see here for the full bit of the quote

“It is unclear what fraction of these savings will be spent. As elsewhere, these savings are highly unevenly distributed across UK households. In its latest projections, the MPC assumed around 5% of savings in aggregate would be spent. This is a conservative estimate. ”

So in essence he has his own view on the split between forced and precautionary savings as does the ECB, the FED, other members of the MPC, David Rosenberg in the US, you, me and so on…

Experience tells us that after major shocks the level of precautionary savings remains higher than before and often for extended periods (hence the weakness in OBR forecast). But at the end of the day, no one knows the exact split. Haldane may well be wrong, but he is not a fool (far from it).

Any0one who can say on average we are better off when he knows how widely unequal is the spread of income and wealth in the UK is a fool.

But that may be too kind.

[…] comes from Andy Haldane’s speech for the Bank of England last Friday. What it shows is that the Office for Budget Responsibility, which is the source of the current […]

there is of course the big elephant in the room , my area, the psychology of a population coming out of a pointless painful decade of austerity listening to the usual suspects talking up low taxes for big business and knowing now what that means for them in terms of lower wages , and stealth taxation .Higher prices for basics like foodstuffs are as even the most ardent brexiteer now admits on the way. and millions of people got their first taste of the supposedly “over generous “ Universal credit and all its kafkaesque nightmare of contradictions and behaviour requirements in return for less in a month than many would have spent on a weekly food shop previously.

like others in this thread I cannot see much in the way of bulk spending after all the internet supplied most non essentials (including my new mattress) , I can see a short hoopla in the pubs and restaurants and I can see many hunkering down after that looking for ways to navigate the new normals

it’s a very worrying time for all of us

Agreed